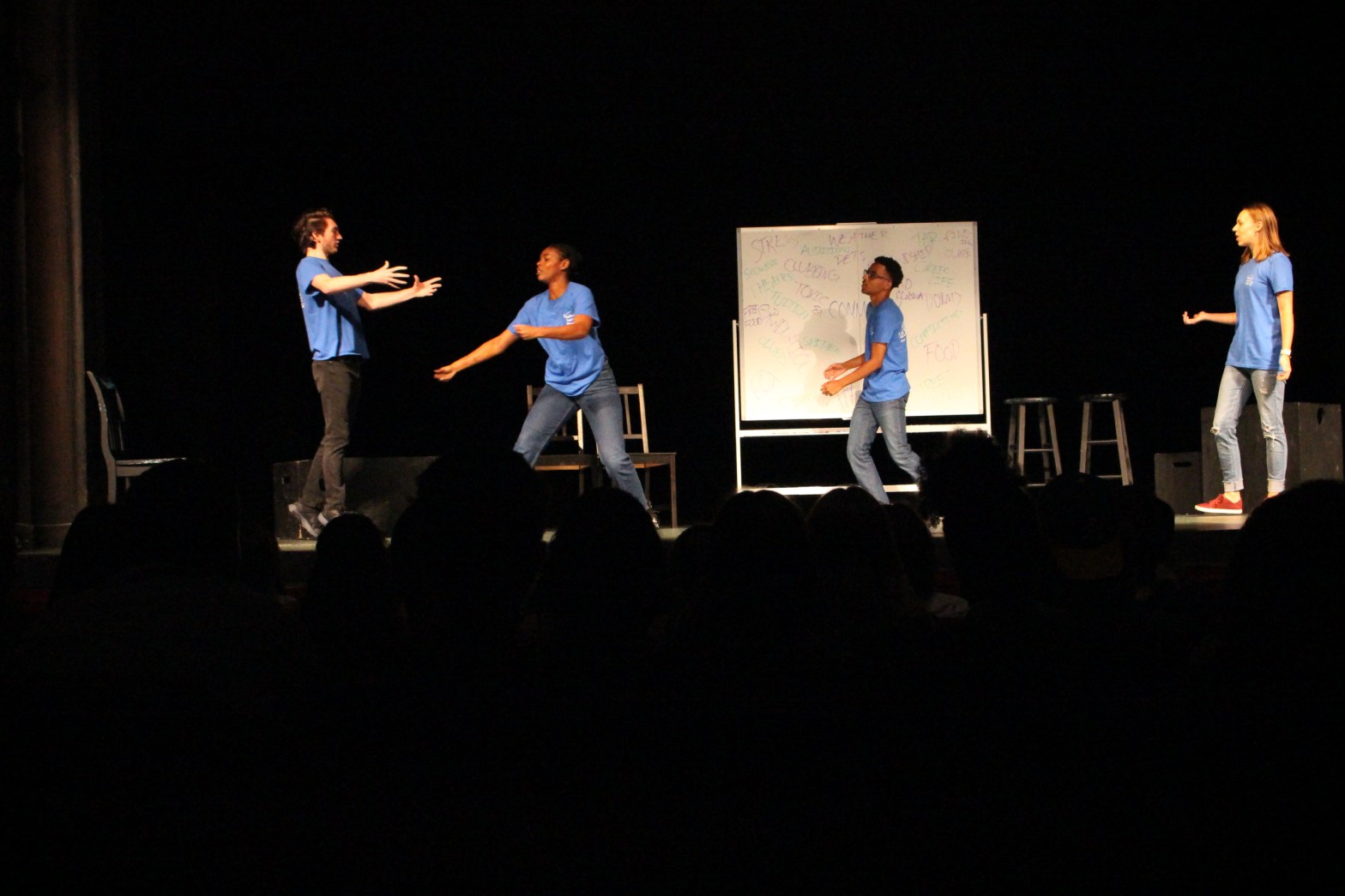

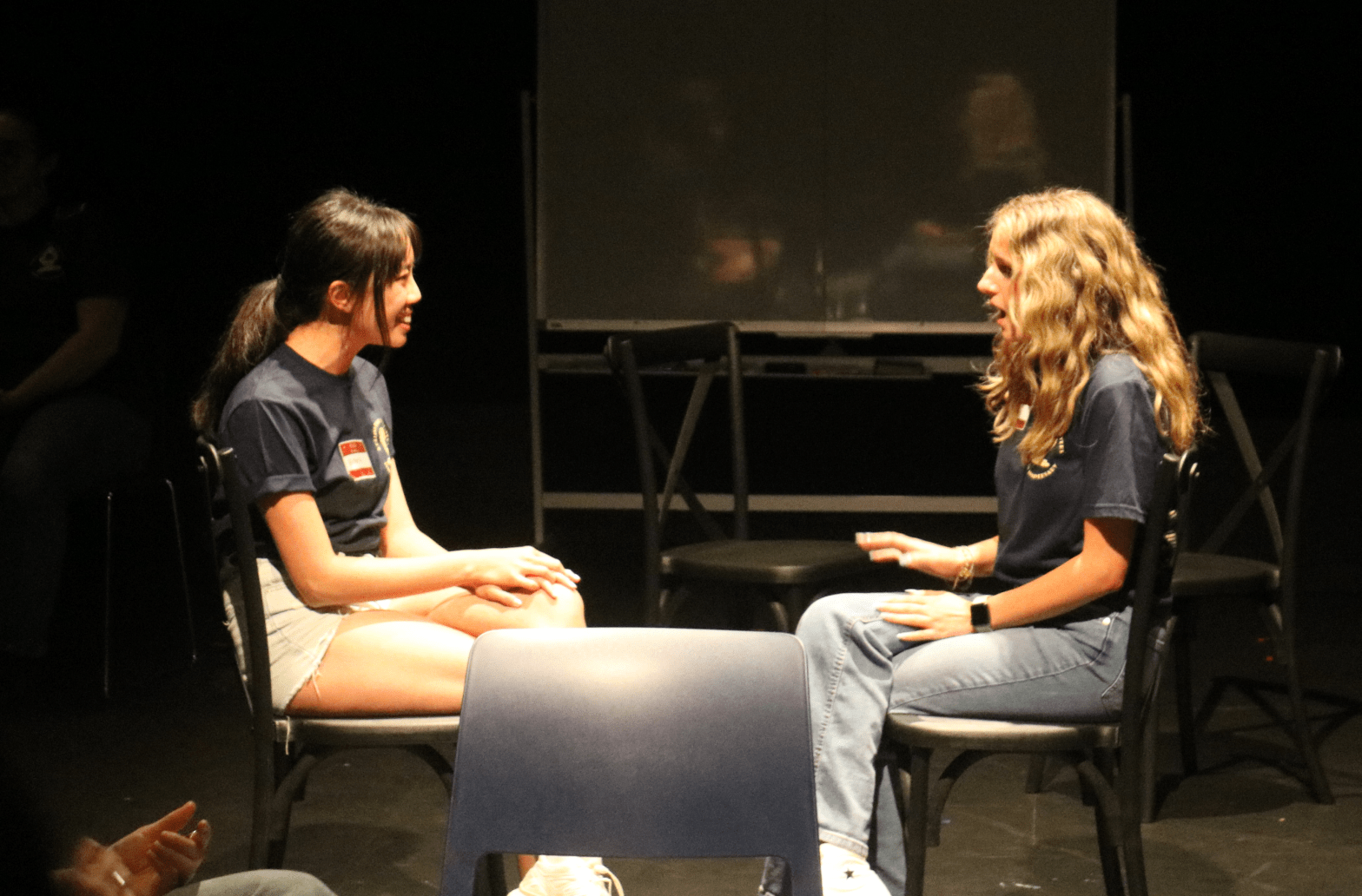

This is another flashback to my high school improv days with United TheatreSports. I’ve seen the game used as a larger all-play warm-up, but my first experience with the format assumed a four-player team, and that’s what I’m outlining below. I’ve woven the example through the definition for clarity.

The Basics

An initial ask-for is obtained that serves as the launching point for a solo scene from Player A.

Player A begins in a kitchen, stressing over getting an important “first date” meal just right. As they are straining the pasta in the sink…

A second player (B, in this case, though the order shouldn’t be set ahead of time), calls out “Spacejump” which freezes the action. This offstage player then enters the stage and uses the existing physical pose to inspire a completely new scenario.

After calling “Spacejump,” Player B enters and quickly takes A’s outstretched hands, endowing the existence of a small bird that has fallen from a tree. “You did the right thing getting me, son…” Both characters carefully construct a small bed out of cotton buds and just as B begins to feed the bird with an eye dropper…

A third player, C, repeats the process and announces “Spacejump” when a new, interesting position has been created. They now join A and B and initiate a whole new premise that incorporates the given physicalities in a whole new way.

Player C assumes the role of a pedantic professor and nervously observes their incompetent students. “Now, if you’ve done the experiment correctly…” The two students explain their incompetence as the chemicals react in an unanticipated way, forcing the three scientists to dash behind the counter for cover…

The fourth and final player, D, gives the cue to freeze the action, and then places themselves into the image, beginning a fourth unique story – in this case four teenagers breaking into a principal’s office to perform a senior prank.

Player D, holding up a key, “It took me a lot to get Principal Enos’ key. You’ve got all the toilet paper…” The scene continues with the four students making their way into the office and covering everything with toilet paper, until…

When all teammates have entered the scene, the game shifts to becoming exit driven (rather than entrance driven). Instead of freezing the action, the last player in now cues the scene change by coming up with a justified reason for an exit. When they successfully leave, the remaining players freeze for a moment, before returning to the prior scenario.

Player D hears a noise and runs out of the office to investigate, leaving A, B, and C behind. After a second of transition, the action return to Player C’s premise…

Players A, B, and C are now standing outside the remains of the science building, justifying their prior poses in the process. They bemoan the disastrous experiment, until C leaves to inform the Provost…

Players A and B now remain in new poses which they incorporate into B’s world of the rescued bird. Parent and child now release the chick back into the wild. B realizes they have forgotten their camera, and they rush offstage to get it…

Player A now remains in a new pose but in their original world, the kitchen. They put the finishing touches on their special meal, before there is a knock at the door. They make themselves presentable, and announce “Coming…”

Blackout.

The Focus

The mechanics of this game, though a little complex to digest initially, are closely related to Freeze Tag structures (here). Subsequently, you’ll want to pursue clear freezes, strong justifications, and physical bravery throughout to keep the energy and risk high.

Traps and Tips

1.) Pace. Give each scene its due. There can be a tendency to rush the entrances if you’re not careful, but you’ll want to make sure the vignettes have enough detail to stand on their own feet. Without memorable relationships and specifics, there won’t be a lot to draw upon when you rewind through the four scenarios on the way back to the original scene. Often, the pacing when you’re revisiting the scenes helpfully becomes a little tighter, but don’t surrender to this rush too quickly.

2.) Move. It’s standard advice for all freeze/justify games, but make sure you’re prioritizing the physical world of each environment. This doesn’t mean just wandering aimlessly around, or engaging in over-the-top action that doesn’t connect to anything or shine light on your characters, but if you’re inclined to a talking heads style of play, the spacejumps can become a little anticlimactic if the poses all start to feel same-y. (And, as is the case with all justifying scenes, be wary of replicating the previous action in the following vignette – a dancing duo shouldn’t just become a different dancing duo with a coach…) It’s also good form to make sure everyone has had an opportunity to justify (and perhaps change) their position before cueing the next adjustment.

3.) Jump. Especially when you’re adding players, make sure you’re honoring the “jump” in “Spacejump” and get yourself onto the stage quickly and with energy. It’s okay to then have a moment of joyful frozen terror as you figure out your first move. (Incoming players should be given the right of way to define the new world, so no one should generally move or speak until you understand the arriving player’s idea.) My standard advice for freeze games holds true here as well in that you’ll be better served by pausing the action at some generically interesting moment, rather than waiting until how you know what you want to do with the scene. Invariably, waiting until you’ve got your idea will result in the poses moving beyond that moment anyway and then it’ll look like you’re forcing an old choice into a new situation.

4.) Leap. And also embrace the leaps and bounds of the scenes themselves. One of the greatest gifts of the growing and shrinking nature of the game (an alternate name for the structure, as well), is that a great deal may have happened between the first and second appearance of a premise. It’s generally accepted etiquette that players should assume the same characters as they embodied when each story was introduced (so B should still be the parent, and A the son when we get back to our bird rescue scene), but you can be much more inventive when it comes to the place and time. In this manner, our scientists reappear in the rubble of their laboratory, and our bird keepers flash forward to when the animal has full recovered. When you scroll back through the scenes, it’s kind to allow the “owner” of the premise to make the first choice just to enable these types of creative moves.

In performance

As the long-winded explanation above reveals, this is a bit of a tricky game to describe efficiently to an audience, so don’t get lost in the minutiae. Concentrate on the key dynamic – that you’ll be improvising a series of scenes based on unique poses – and trust that they’ll pick up the other pertinent elements as it goes.

Cheers, David Charles.

www.improvdr.com

Join my Facebook group here.

Photo Credit: James Berkley

© 2025 David Charles/ImprovDr

Game Library Expansion Pack I